Care

Discover the Benefits of Copepods in Aquariums: From Algae Control to Live Feed for Marine Organisms

Discover the Benefits of Copepods in Aquariums: From Algae Control to Live Feed for Marine Organisms

Copepods Evolved to Devour and to be Devoured

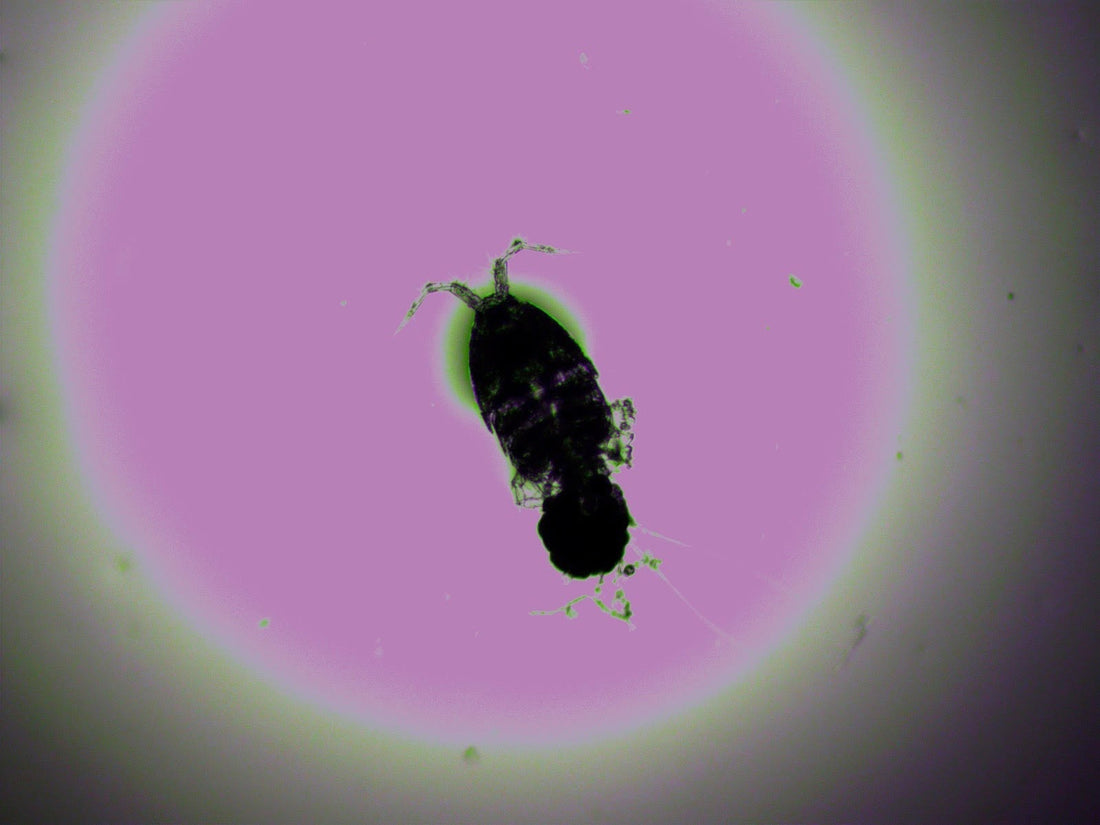

Microalgae are the most important primary producers on the planet, because they take inorganic material and convert it into precious nutrition. This microalgal nutrition finds its way to every animal on the planet, but only after being consumed by one of the great grazers. Copepods are microcrustaceans which graze on algae in the wild and in our aquariums. If introduced and allowed to thrive, copepods will eventually establish themselves in most well-aged freshwater, brackish and saltwater aquaria. Like algae, there is a huge amount of diversity amongst the copepods, with different types/species specializing in different prey items. Harpacticoid copepods (Tisbe, Tigriopus) can be seen crawling on glass and rock work. These are adept at preying on algae attached to these surfaces. They can also crawl deep into crevices seeking detritus. In contrast, Calanoid copepods (Acartia, Parvocalanus, Pseudodiaptomus) actively swim in the water column, where they prey on suspended algae and organics. Cyclopoid copepods (Apocyclops) do a mixture of the above two behaviours but are adept at consuming ciliates and other pests. There are many more general types of copepods than these,with thousands of species, each adapted with its own tools to “clean up” algae, detritus and pests.

Today, only a handful of copepod species have been studied for direct application in aquariums. However, the species that have been embraced... are a hit!!!

Let me explain, since copepods were embraced in aquaculture the following has happened:

- Species which often starved to death before (mandarins) are now keepable and tanks can be conditioned to host enough pods to sustain them.

- New species can be aquacultured using copepods as live feed for their larval states. More and more species are being bred in captivity for the first time because their babies eat pods!

- The industry has ‘new eyes’ for the micro critters in aquariums, which in reality, are integral to the greater functionality of any ecosystem.

Why Pods are the Ideal Live Feed

- There are many species which can survive and establish in aquariums, rewarding each feeding with a greater chance of creating a self-sufficient population.

- Many species (Tisbe biminiensis) act as micro cleanup crew, turning algae and detritus into more pods!

- Copepods look small to us, but we can only see adults (1000 microns), their nauplii (babies) are 50-100 microns and free-floating. This makes them ideal for feeding corals, small-mouthed filter feeders and larval fish!

- Copepods retain golden fats (DHA/EPA) in their tissues much longer than Artemia or Daphnia--making them far more nutritious to marine organisms.

In short, copepods are a godsend to the reef industry, or rather… recognizing the work copepods were already doing is the godsend. Now that the industry recognizes this powerful tool, more and more hobbyists can intentionally deploy them to stabilize all kinds of new ecosystem designs, feed the unfeedable and breed the unbreedable!

With Pods Anything is Possible

Literature Consulted

de Lima, L. C., Navarro, D. M., & Souza-Santos, L. P. (2013). Effect of diet on the fatty acid composition of the copepod Tisbe biminiensis. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 33(3), 372-381.

Marcotte, B. M. (1977). An introduction to the architecture and kinematics of harpacticoid (Copepoda) feeding: Tisbe furcata (Baird, 1837). Mikrofauna Meeresboden, 61, 183-196.

McEvoy, L. A., & Sargent, J. R. (1998). Problems and techniques in live prey enrichment. Aquaculture Association of Canada, 98(4), 2.

Nanton, D. A., & Castell, J. D. (1998). The effects of dietary fatty acids on the fatty acid composition of the harpacticoid copepod, Tisbe sp., for use as a live food for marine fish larvae. Aquaculture, 163(3-4), 251-261.

Parrish, C. C., French, V. M., & Whiticar, M. J. (2012). Lipid class and fatty acid composition of copepods (Calanus finmarchicus, C. glacialis, Pseudocalanus sp., Tisbe furcata and Nitokra lacustris) fed various combinations of autotrophic and heterotrophic protists. Journal of plankton research, 34(5), 356-375.